- Home

- Lauren Kate

The Orphan's Song Page 2

The Orphan's Song Read online

Page 2

It wasn’t that Violetta was carefree; she only seemed that way to Laura, who turned toward her worries as much as Violetta tried to escape them. It was why she spent so much time at her window, imagining herself beyond it.

Laura stuffed a loose curl back into the great brown bun of her hair. “Of course, you didn’t hear.”

“Hear what?” Violetta didn’t know how long she’d been at the window. This happened on days when she’d had the dream.

The wheel, the woman. That song. Eleven years had passed since that night, but she remembered the dark race downstairs as if it were yesterday. She’d been the only one who knew he was there, stuck. The only one who could help. She’d never been so near a boy’s alien body. He’d still been sleeping when she pulled him from the wheel.

Years later she had realized that his mother must have drugged him. That he hadn’t even heard the woman’s song.

Whenever Violetta dreamed that song, it rendered her waking life muted and pale. She struggled to go about her responsibilities as usual: rising at sunrise, praying aloud by rote—first the Angelus, then a prayer for suppression of heresy, one for their most pious republic, one for the benefactors and the governati of the Incurables, and on and on—just as all the other murmuring voices did in the rooms to the left and right of hers.

Before mass she had taken her breakfast of porridge and cream as the prioress’s wide hips moved between the rough wood tables, spouting sacred readings in her corrosive whisper, daring any of them to gossip or to giggle. And then the morning had passed with three hours of music lessons—first with the full music school, second with a smaller coterie of singers, and finally with her private tutor, Giustina.

Giustina was beautiful, twenty-four, and the lead soprano in the coro. She was known as bella voce throughout the city, and even beyond the republic of Venice. Tourists traveled from across Europe, paying dearly to hear her perform. Last summer, she astonished Violetta, selecting her as one of two apprentices. Violetta still could not be sure what Giustina saw in her, but her sottomaestra’s patient generosity inspired her to try her best.

At the moment, she was meant to be reading the latest corrections to her sheet music, practicing her trills and passaggios. Giustina would test her on them later, before compline, the prayer at end of day. But Violetta hadn’t even looked at the pages. The moment she’d been free to close herself in her room, she’d drawn near the window, felt the warmth beyond it, and let her mind fly away.

The dream song haunted her, those words she could never sing aloud.

I am yours, you are mine . . .

It had become her song. But who or what was she addressing? Sometimes she still thought of the boy she had pulled from the wheel that night. Before Violetta had left him near the embers of the kitchen hearth, tucked beneath a folded tablecloth, she had discovered the small painting clutched in his hand.

It was half a painting, really, a thin piece of wood, splintered from being shorn diagonally in half. It hung from a broken chain, as if it had once been a pendant. It featured a naked woman. Half a woman. Face and breasts and a belly covered by waves of flowing blond hair, the same shade as the boy’s. Dark eyes cast into the distance, her mouth open in song against a blue sky.

The boy’s mother must have kept the other half. Most orphans at the Incurables had some such token—part of a painting or a swath of patterned fabric—proof of a bond, should destiny ever reunite mother and child.

Violetta had none. She didn’t believe in such fantasies.

She’d never seen that boy again, so separate were the lives of boys and girls at the Incurables. She didn’t want to see him, though he was always with her. The song meant for him haunted her, gave words to the part of herself she most wanted to deny—that someone had done the same thing to her. She hoped he had no memory of his abandonment, that he never had to think upon that night. Likely by now he had moved on from the orphanage to an apprenticeship somewhere in the city.

“Violetta!” Laura took her arm. “Porpora is back.”

Violetta jumped to her feet. “Why didn’t you say so?”

That year, the Incurables had commissioned the famous Neapolitan composer Nicola Porpora to lead the coro. He was the final authority, determining which girls advanced and which did not. Even the youngest students, tiny children six years of age, straightened their shoulders and hushed their gossip at the mention of his name.

Those Porpora chose for the coro could look forward to years of intense collaboration with the brilliant, tightly wound composer and to regular performances before admiring crowds. The women of the coro enjoyed leisure time, more frequent outings, better food, and wine. Some of them received letters from important Venetians or European tourists who traveled just to see them perform. A portion of the sizeable earnings from their concerts was saved in a special dowry.

The girls not chosen for the coro became figlie di commun, the ordinary women of the orphanage. They served as nurses to the syphilitics on the first floor, or toiled in menial tasks like laundry and lace making, sewing and dyeing the thick wool cloaks that inimitable shade of midnight blue. Some became zie and cared for foundling babies. Figlie di commun worked for the orphanage until they were forty, and then they were sent to a nunnery. The only possibility of escape was to be sold off as a servant. But worst of all, the music simply stopped. There were no more opportunities to practice or perform if you were a figlia di commun.

This horrified Violetta. All they knew of life was music, and to have it taken away? She and Laura had pledged to each other that they would not accept this fate. Deep down, Violetta suspected that both of them knew Laura would be fine, but that Violetta, with her tendency toward daydreams, might not make the cut.

The maestro had been abroad for all of August and half of September. Lessons relaxed in his absence, but no longer. Porpora would stay on through the fall, through the festival of carnevale, as the coro prepared for their most important season of performances, Advent. For Violetta and Laura, and each of the sixty-two younger girls in the music school, Porpora’s arrival meant a trial by fire.

“He wasn’t meant to return until next week,” Violetta said.

“He’s early,” Laura said. “And he wants to hear us. In the gallery.”

“The gallery?” That was where the coro girls performed. Violetta had been in its anteroom many times, fetching sheet music for Giustina, but she’d never set foot in the special enclave that looked down over the entire church through a gilded grille. The music school girls practiced in a stifling, windowless chamber above the apothecary. It stank of the holywood tea brewing for the syphilitics downstairs.

“You’re already late,” Laura said, “and you’re not leaving this room with your hair like that.”

“What’s wrong with my hair?” Violetta tugged the thick, dark rope that hung to her waist. There was no mirror in her chamber. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d brushed her impossible hair.

“Leave it to me,” Laura said, moving behind her, standing astride Violetta on the creaking bed, her toes nudging Violetta’s thighs through her slippers. “You start warming up. Scales. And, Madonna, stockings!”

Violetta worked the scratchy wool stockings up her legs, fastening them with a ribbon just above her knee. She grumbled when Laura undid her days-old braid and pulled dense knots from her hair.

While Laura’s fingers gathered and combed, Violetta straightened her back and breathed through a fibrous wall of nerves. She pulled on her tongue, flattening it between her fingers as she moved through three octaves of scales, as Giustina had taught her to do.

“When you sing,” the sottomaestra had said, “you must think of what you want to say to the world.”

When Violetta sang, she was barely confident enough to want to be heard, let alone to convey a message. She found it hard to imagine the world might be listening to her.

&n

bsp; She turned the question back on Giustina. “What do you want to say to the world?”

Giustina pressed both hands to her breast and sighed. “Love is here.”

Violetta’s eyes had pricked with tears, for she felt there was nothing higher any musician could aspire to. And she felt hopeless. She would never be able to sing something so brave and essential to the world. She wanted to see and hear the world and be inspired by it. She couldn’t imagine returning the favor.

Giustina had squeezed Violetta’s shoulder and said softly, “Don’t worry, you’ll find it.”

Would she? Violetta was a soprano, but a faint one, and despite her years of practice and prayer, her voice still stretched to reach the highest notes of the complicated arias she loved best. Sometimes she felt fear holding her back. If she could only make the coro and relieve herself of this anxiety, her voice might come into its own. She wondered what it felt like to perfect an aria, to sing as Porpora intended—or better. But when she thought of asking Giustina, she knew this was not something one could express, much like the buried root of Violetta’s own longing.

The best moments were those when she felt her voice blend with the other singers’. When she felt a part of the music instead of alone. Then Violetta longed to be nowhere else, caught in the joyful embrace of a song.

But today the dream had its grip on her, and she felt unworthy of the music. Why did the maestro have to arrive now?

At least Laura’s presence was a comfort. Soon she and Violetta synchronized—as Violetta moved toward the upper registers of her scales, Laura spun her hair into a neater, tighter braid. Music was in all the girls so deeply that they made it out of everything they did: the syncopated clanks of their spoons against their bowls at dinner, the soft percussion of their footsteps to nightly confession, the tenor whistle of their piss into porcelain pots.

“Hold your notes. What’s wrong with you?” Laura said as she secured Violetta’s hair. She came around to stand before Violetta, smoothed a wild cowlick, nodded at her work. She touched one finger under Violetta’s chin, raised it, looked into her eyes.

“You had the dream?”

Violetta nodded, quiet but not ashamed. From the years she’d slept in the nursery she knew that nightmares were common. Laura knew Violetta dreamed of one thing again and again, and that when she did, it brought great sorrow, but she had never asked Violetta for details. And Violetta had never clarified; she had never asked about Laura’s own painful dreams. What would have been the point? Each girl here had so little from her time before, when she had been figlia di mamma—the daughter of a mother—not just figlia degli incurabili—a daughter of the Incurables.

For Laura, it was enough to know Violetta had the dream and that the day would be shaped by its ghost. And so Laura’s hand found Violetta’s, a reassuring secret music in the pressure of their palms, in the sound of their slippers as they ran for the bridge.

The bridge was a short, windowless passageway, no longer than a gondola, accessed through the third floor of the dormitory. It arced over the courtyard and connected to the church in the center, opening onto a small anteroom where the coro girls warmed their voices, tuned their violins, and broke in new oboe reeds before performances.

Beyond a white door at the far end of the anteroom was the treasured performance space of the coro: the singing gallery. A chest-high marble parapet enclosed the gallery, and, above the parapet, the famous brass grille of sculpted orange blossoms was the object of widespread fascination. The grille was intended to obscure the performers from the eyes of the church below—and vice versa—but when Violetta sat in her pew downstairs with the other music school girls and gazed up, she could discern which girl was which.

How powerful and mysterious they had looked behind those gilded orange blossoms. How she always wanted to be one of them. She suspected most parishioners spent the full mass straining to see the angels making music on the other side.

“Are you ready?” Laura asked at the door to the gallery.

Violetta’s throat felt troublingly tight. She squeezed Laura’s hand. “I can’t believe you left rehearsal to come find me.”

The corners of Laura’s mouth flicked up. “We made a deal.”

Laura cracked the white door open, pushed Violetta’s shoulders gently forward, and the two of them slipped inside the gallery. Violetta ducked below the parapet. She did not wish to be seen by Porpora or the prioress, conducting in the nave below, until she was in her place.

How small the gallery was, only two standing rows packed tightly, the upper level for strings, woodwinds, and the organist, the lower level for singers. Violetta quickly gauged that only half the music school was there—the girls of fourteen years and older who were approaching consideration for the coro. Each performed for their life. And here came Violetta, like a lost dog underfoot.

Laura made their late entrance look easy, taking her place near the door where her violin was waiting. She’d picked it up and had fallen in with the music before Violetta even chose the smoothest route to her place at the front. She tried to weave between the singers. Most inched back so she could pass before them, wishing to hurry along the distraction. None of them stopped singing the “Alleluia.” It was a short piece of music with violin and timpani parts that complemented a range of singers—now the contraltos, now the sopranos.

At last, she arrived at her place, third from the end, between Olivia and Reine. Olivia made room for her; Reine would not give an inch. If Reine and Violetta had disliked each other from the moment Reine arrived at the Incurables a year ago, their animosity had swelled when Giustina chose them both as her apprentices.

Reine was not Venetian. She was not even an orphan. Her rich Parisian parents had elected to send her to the Incurables. No amount of money could buy a rich girl of the republic a spot. Only foreigners were permitted to feign orphandom for a price.

She liked to provoke Violetta. “Do you dream of the whorehouse where your mother birthed you, took one look at your bug eyes, and abandoned you here?”

“My mother is music,” Violetta replied with such conviction that she silenced the French girl. She strained inside to steady her voice as she spoke a portion of the truth: “In my dreams, she sings.”

Reine was a marginally better singer, but she postured as if she were the coro’s greatest star. When the day came for Giustina to leave the coro, only one of them would move up.

Violetta inhaled and tried to make herself brave. She rose to stand next to Reine, opening her mouth and joining the song.

“Nei secoli dei secoli, nei secoli dei secoli. Alleluia.”

Her eyes widened as she adjusted to her surroundings. Through the grille the nave was lit by broad beams of sunlight streaming through the clerestory. She saw the rows and rows of empty pews and tried to imagine singing to a thousand people. Her chest expanded with unexpected joy.

She saw the brilliant Tintoretto hanging in the apse, depicting Saint Ursula and her eleven thousand virginal maids. It was a reminder of what the Incurables girls aspired to: musicians, yes—but nothing before virgins.

And then she saw the sharp flick of the prioress’s head. She noticed Violetta.

She assumed her most virginal expression, casting her eyes to the heavens. She lengthened her spine, clasped hands over her belly, puffed out her chest. She hit the notes perfectly, defiant. She’d pay for this later, but canings and humiliating public confessions had long been part of Violetta’s life. It was Porpora she didn’t wish to aggravate.

The guest of honor stood next to the prioress, swaying to his music, eyes mercifully closed. He was not interested in the music school students so much as he was interested in hearing his new composition. He did not know these girls’ names, their voices, their special talents and limitations. He saved this attention for those chosen for the coro.

A bloated man in midlife, with a wispy gray w

ig and round, pink cheeks, their maestro didn’t look like the man who would compose such astonishing music. He was no Vivaldi, whose red hair and intense gaze had arrested Violetta when she studied his portrait. She had found it sketched on the library copy of a libretto Vivaldi had written for the rival coro at the Ospedale della Pietà, across the Grand Canal. But then who was Violetta to judge appearances? Her own face hadn’t grown to accommodate her huge dark eyes, which made her feel like a beetle when she passed her reflection in the glass. And she still didn’t have any breasts.

The sopranos’ notes were rising. Violetta had to arch her back to get them out. Her shoulder probed Reine’s, who responded by elbowing Violetta’s ribs. Violetta’s voice snagged as she wheezed, but she recovered quickly, shooting Reine a dangerous look.

Now the music moved from “Alleluia” to a recitative, easier to sing. The lyrics were more like talking, and the good ones told a story. The performers seemed to relax, but as Violetta’s lips moved through the memorized verses, her heart swerved to another song.

I am yours, you are mine . . .

She tried to push it away, to channel the other concentrating girls. But the dream song possessed her, weaving its way into the recitative. It wanted to be sung. From the corner of her eye, she saw spit flying from Reine’s mouth, and she hated her. Reine, whose parents sent great sums of money to the school along with multipaged letters to their daughter, lace handkerchiefs misted with sickly sweet perfume. Reine, who did not know what it was like to have been abandoned. Reine, who would surely make the coro over her.

Another jostle of shoulders. Violetta couldn’t tell whose fault it was, but she rolled her shoulder forward, edging in front of the girl. Reine rolled hers forward, edging in front of Violetta. Violetta wished deeply to be free of this gallery, of this cruel girl, of the dream song she could not unhear. And all of that eventually drove her to lift her foot and stamp down hard on Reine’s rich toe.

She would have wagered almost anything that Reine would sing through the pain, plan a dark, future revenge. She never expected the French girl to scream.

Fallen in Love

Fallen in Love Last Day of Love: A Teardrop Story

Last Day of Love: A Teardrop Story Teardrop

Teardrop Passion

Passion Fallen

Fallen Torment

Torment Waterfall

Waterfall Rapture

Rapture Unforgiven

Unforgiven The Betrayal of Natalie Hargrove

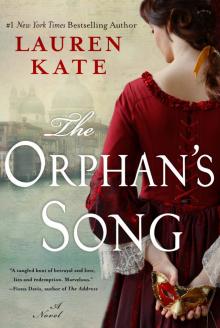

The Betrayal of Natalie Hargrove The Orphan's Song

The Orphan's Song The Fallen Sequence: An Omnibus Edition

The Fallen Sequence: An Omnibus Edition Teardrop (Teardrop Trilogy 1)

Teardrop (Teardrop Trilogy 1) Fallen_Angels in the Dark

Fallen_Angels in the Dark